“Do not separate text from historical background. If you do, you will have perverted and subverted the Constitution, which can only end in a distorted, bastardized form of illegitimate government.” ~ James Madison

“A treaty cannot be made which alters the Constitution of the country, or which infringes and express exceptions to the power of the Constitution.” ~ Alexander Hamilton

“The Constitution is not an instrument for the government to restrain the people, it is an instrument for the people to restrain the government — lest it come to dominate our lives and interests.” ~ Patrick Henry

“The Constitution of most of our states (and of the United States) assert that all power is inherent in the people; that they may exercise it by themselves; that it is their right and duty to be at all times armed and that they are entitled to freedom of person, freedom of religion, freedom of property, and freedom of press.” ~ Thomas Jefferson

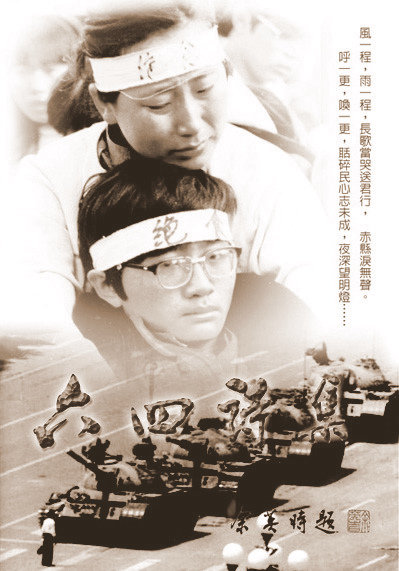

“A Constitution of Government once changed from Freedom, can never be restored. Liberty, once lost, is lost forever.” ~ John Adams

James Madison

I am still trying to comprehend the majesty of all these great men coming together in crafting this noble document, and every time I read the Constitution I cannot help but think how magnificent this instrument of our democratic system is.

But I know that we should not take things for granted. This Constitution did not arrive automatically as a mere follow-up of the Declaration of Independence. In fact, America was at a crossroads right before the 1787 Philadelphia Convention.

Let’s just go back to the year before. 1786 was the 10th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, but the young nation was not as jubilant as we might have imagined in celebration. Dark clouds in all shades were floating over the country. Form his plantation in Virginia, George Washington lamented the steady stream of diplomatic humiliations suffered by the young Republic. Fellow Virginian James Madison talked gravely of mortal diseases afflicting the confederacy. In New Jersey, William Livingston confided to a friend his doubt that the Republic could survive another decade. From Massachusetts the bookseller turned Revolutionary strategist, Henry Knox, declared, “Our present federal government is a name, a shadow, without power, or effect.” And feisty, outspoken John Adams, serving as the American minster to Great Britain, observed his nation’s circumstance with more than his usual pessimism. The United States, he declared, was doing more harm to itself than the British army had ever done. Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Monroe, Robert Morris – in short, men from every state – agreed that a serious crisis had settled upon the nation. [1]

The stage was set for the 1787 Philadelphia Convention. But to most delegates selected from the 13 states, it was not clear what the convention was about. However, that was not the case for James Madison, he knew the task. He wanted to see the creation of a new government. The young Virginian went to Philadelphia way before anyone else, and determined to accomplish what seemed an insurmountable assignment: steering the convention away from amending the Articles of Confederation towards creating a brand new constitution. But anxiety started building upon him, for there was no encouraging sign that even the delegates were to come. Although the time alone there was good for him to complete drafting his proposal ready to be submitted to the convention.

Then, in a Sunday morning, May the 13th to be exact, Madison woke up to a rousing sound of cheering mixed in chiming bells and firing cannons. He jumped out bed knowing precisely what just had happened – something he had been worrying greatly that might not happen – George Washington arrived, as a delegate from Virginia! The death of his brother earlier that year and his own health had made Washington’s attendance to the convention uncertain. Washington’s arrival not only lifted Madison’s spirit, but gave him great confidence that the convention would take place. Surely, with the presence of Washington, Madison was able to establish much needed support from a number of Philadelphia’s own influences, including the 81 year old Dr. Benjamin Franklin. Most importantly, the delegates started to arrive, and the required quorum was soon exceeded. The conversion went underway, with Washington being unanimously selected to preside the conversion. The date: May 25th, 1787. The place: The Pennsylvania statehouse, better known as Independence Hall.

Madison waited patiently. He wished some of his colleagues were there with him. The most notable politicians missing were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams (both of whom were overseas working as diplomats), as well as Samuel Adams, Thomas Paine, and Patrick Henry. But there was a strong coalition in the forming, including his fellow Virginians and the delegates from Pennsylvania. On May 29, Edmund Randolph, on behalf of the Virginia delegation, submitted fifteen propositions as a plan of government to the convention. On the next day, the Convention devolved into a committee of the whole to consider the fifteen propositions of the Virginia Plan seriatim. As one could imagine, debate about the treatment for large and small states heated up, representing the two arguments were, as expected, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Madison argued that a conspiracy of large states against the small states was unrealistic as the large states were so different from each other. Hamilton argued that the states were artificial entities made up of individuals, and accused small state representatives of wanting power, not liberty. The small States became increasingly discontented and some threatened to withdraw. On July 2, the Convention was deadlocked over giving each State an equal vote in the upper house, with five States in the affirmative, five in the negative, and one divided.

July 5th marked an crucial date. On that day, the committee submitted its report, which became the basis for the “Great Compromise” of the Convention. The report recommended that in the upper house each State should have an equal vote and in the lower house, each State should have one representative for every 40,000 inhabitants.

The Great Compromise ended the rift between the large and small states, and the high quality of the delegates to the convention eased the way to compromise. With the spirit of forming a better federation to protect the freedom of the citizens, the delegates worked intensively for the whole summer. On July 24, a committee of five (John Rutledge of South Carolina, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts, Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, and James Wilson of Pennsylvania) was elected to draft a detailed constitution embodying the fundamental principles that had thus far been approved. The committee, referenced a vast variety of laws and constitutions for ideas, in particular, the British Bill of Rights, submitted its writing to the convention, which was discussed, from August 6 to September 10, in such a vigorous detailed fashion. On September 12, the new Constitution was printed for all delegates. And on September 15, the Constitution was engrossed.

And that led to the signing day – Monday, September 17th 1787. And in the famous painting by Howard Chandler Christy (1873-1952) below, we could identify George Washington, standing on the dais. The central figures of the portrait are Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin and James Madison.

Let me quote Patrick Jake O’Rourke, “The U.S. Constitution is less than a quarter the length of the owner’s manual for a 1998 Toyota Camry, and yet it has managed to keep 300 million of the world’s most unruly, passionate and energetic people safe, prosperous and free.” [2]

That’s what the Constitution means to the citizens of this nation. With the Constitution firmly standing as the foundation of this democracy, again P. J. O’Rourke, “America wasn’t founded so that we could all be better. America was founded so we could all be anything we damned well pleased.” In other words, under the guideline and protection of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, individual liberty is the rights of each and every citizen, who shall be with no fear because under any circumstance he or she understand the protection granted, not by the government, but by the foundation of the nation. “The Constitution of the United States is not a mere lawyers’ document. It is a vehicle of life, and its spirit is always the spirit of the age.” [3]

In this choice of inheritance we have given to our frame of polity the image of a relation in blood; binding up the constitution of our country with our dearest domestic ties; adopting our fundamental laws into the bosom of our family affections; keeping inseparable and cherishing with the warmth of all their combined and mutually reflected charities, our state, our hearths, our sepulchres, and our altars.[4]

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

[1] Carol Berkin: A Brilliant Solution: inventing the American Constitution (2002)

[2] Patrick Jake O’Rourke, source not found.

[3] Woodrow Wilson: Constitutional Government in the United States (1908)

[4] Edmund Burke: Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

Tags: Constitution

Follow me

Follow me in these Social Networks